Russian Nesting Doll: Layers of Architectural Fiction in Pathologic

Original source: westofthewilds on tumblr

Games have acted as a simulation of real physical space for as long as they have existed. Five thousand years ago, stone figures and maps abstracted bloody battlefields into military strategy exercises. In the late 1940s, the US military began using computers to run the same type of simulations. However, the digitization of games within the last century has introduced a new architectural element. Digital space allows game designers to act as architects in constructed game space, which opens new avenues for immersive storytelling.

Within narrative simulation games, there are four levels of architectural fiction to explore: psychological, theatrical, digital, and physical. Within the first, psychological, the player wholly embodies a character and their associated personality, philosophy, and perspective within fictional space. Secondly, the theatrical level acknowledges the existence of the simulation and uses this to comment on its metaphorical, fictional themes. The third, digital level, includes the game itself, and how various design decisions contribute to the fiction. Finally, the physical level explores what, if any, relevance game space has in the real world. Through this framework of abstraction, this paper aims to analyze the architectural themes within the Pathologic franchise from Russian game developer Ice Pick Lodge.

- Psychological

You are Daniil Dankovsky, Bachelor of Medicine and man of science. You are a big city man with big dreams. Your goal is the highest achievement to which a doctor can aspire: to cure death itself. You came to the Town twelve days ago, hoping to find answers in your research. Instead, your battle against death has only grown more hopeless and exhausting. A deadly plague kills thousands by the day. You are one of only three healers in this town; the other two are hardly any help. Soon, The Powers that Be will send the army, and they will ask you to decide the fate of the Town and everyone in it.

The people of the Town do not like you, and you do not like them. Their folksy, backward practices have hindered your every attempt to help them. What’s more, you suspect these practices are the root of the very plague itself—a pathogen released from decades’ worth of congealed bull’s blood beneath the giant slaughterhouse. In the end, you conclude that the Town is hardly worth saving. There is only one thing here of any value: the Polyhedron.

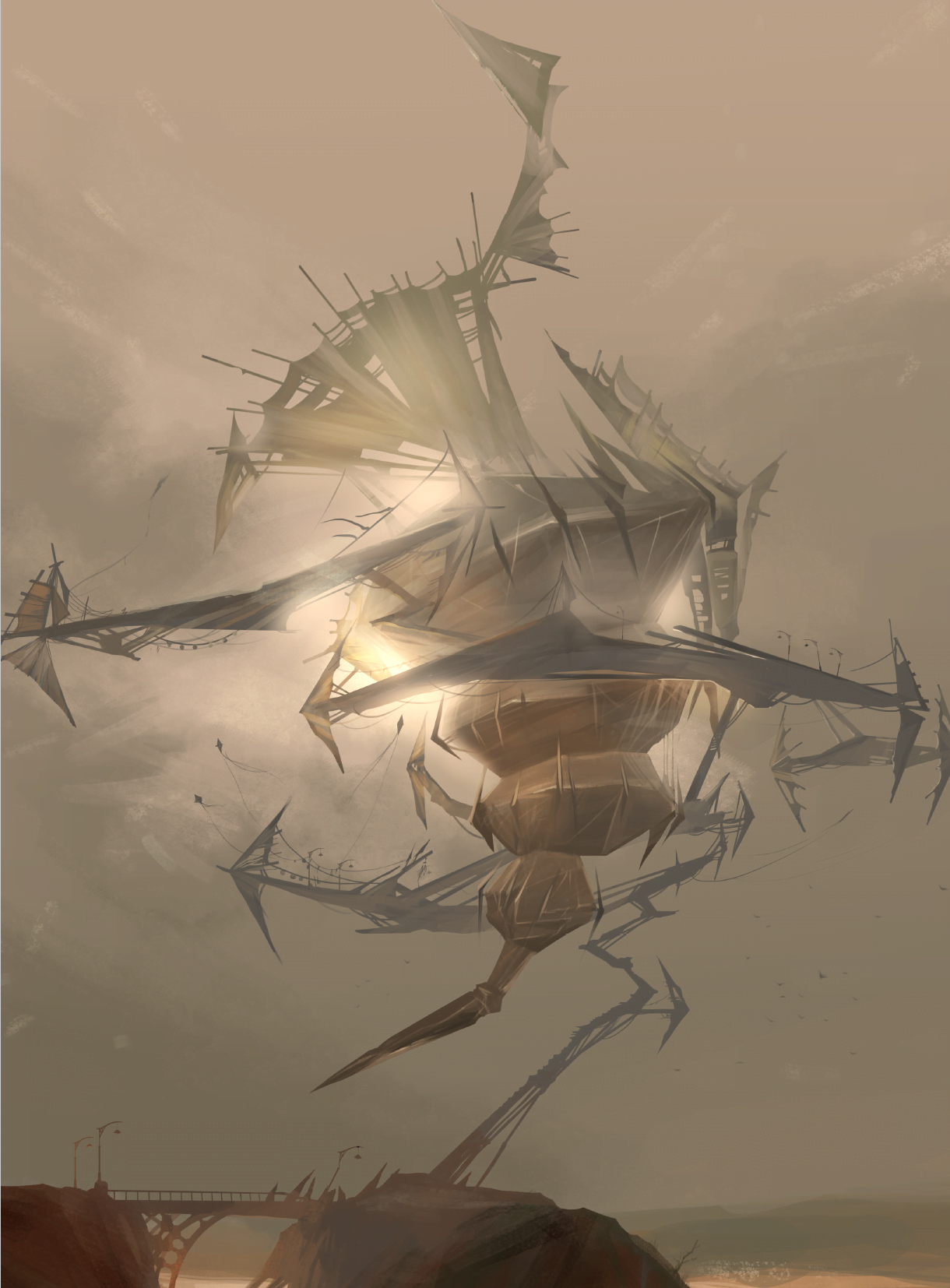

The Polyhedron looms over the town, an even more foreign structure in this already alien landscape. It is an impossible tower held up by nothing, a miracle made reality. If you look closely, it is constructed not from glass, or steel, or wood, but from its own blueprints. It is an idea created from itself,2 but nobody can quite agree on what that idea is. You believe that the Polyhedron is a piece of the deathless utopia you have been searching for. After all, the Polyhedron is the only place in the Town untouched by plague. The local children inhabit the structure and bar adults like you from entry. The children tell you that the Polyhedron makes dreams into reality, and there might be some truth to this. It is the manifestation of the dreams of the architect Stamatin brothers, of Simon Kain, the man who commissioned the tower, and of your own life’s work towards a world free from death.

Another dream pervades the Polyhedron, born from the mind of a man named Vladimir Tatlin. He is not from this town or even this world, but nevertheless, his ideas made their way here from revolutionary Russia. In 1917, class inequality and social oppression sparked civil unrest in Russia, and a new socialist regime took power.3 Meanwhile, the painter Vladimir Tatlin rose to prominence in the Russian avant-garde scene, and would later become known as the father of the Constructivists.4 Constructivism was the artistic side of the revolution, responding to the same core issues of capitalism and exploitation. The core idea of Constructivism was that art and architecture were not, and should not be, purely aesthetic. Rather, by adopting the practical material considerations of industrialism, architecture could become a tool of the socialist revolution.4 Architecture could create a world where a utopian future was actually possible. Tatlin implemented these concepts when he took over the Monumental Propaganda initiative to replace tsarist monuments with sculptures that embodied Russia’s new socialist ideology.5 His magnum opus was a proposal for the Monument to the Third International, a 1700-foot-tall sculptural tower which would serve as the headquarters for Comintern, the Bolshevik organization which advocated for worldwide communism.6 The tower not only symbolized the new age of Russian politics; it was also a tool for progress toward a global Soviet utopia.

You, Bachelor Dankovsky, are not a strict believer in the cause of the Constructivists, as you could care less about socialism. Your role in the revolution against death is a much more pressing issue, and the Polyhedron is to you what Tatlin’s Tower was to believers in Soviet Russia: a tool of the revolution. It not only symbolizes progress; you believe that it can make progress possible. If this miracle tower can bring about the utopian future, then it must be preserved above all else. On your final day in the Town, when the arrival of the army forces you to choose between the tower and the Town, there is no contest. The Polyhedron’s shadow falls across the wreckage of the Town, shelled to rubble by the military’s firepower.

You’ve won. The plague is defeated at the cost of the Town. And yet, something about this victory feels wrong. Dreams of Soviet utopia appear in the periphery once more, only this time, you are able to see the whole picture. Tatlin’s Tower remained forever unbuilt.4 It never became the headquarters for Comintern, and Comintern never succeeded in creating a global communist utopia. In fact, even a Russian communist utopia remained out of reach. An estimated 60 million people died as a direct result of the Soviet regime’s policies.7 The Monument to the Third International was a tool, but it was one of unrealized promises and propaganda rather than utopia. As you watch the Kain family gather around the base of the tower they commissioned, you begin to fear the same may be true of the Polyhedron. Maybe the tower was simply a piece of propaganda created to serve the interests of the powerful and wealthy. You, a doctor, sacrificed the lives of thousands under your care for the sake of a better world for a theoretical humanity elsewhere. But what if that utopian better world never comes to fruition? Brutal utilitarianism becomes simple brutality. Utopia itself becomes a tool of propaganda to justify murder.

You close your eyes—reality restarts.

When you open your eyes again, you are someone new. This time, you are Artemy Burakh. You go by other names, too: the Haruspex, the surgeon, the ripper, the blood, the Abattoir. Unlike Dankovsky, you are a native of this town, a descendent of both the Townsfolk and the local indigenous group called the Kin. You value the Town’s people, its traditions, its land. You see what the Bachelor could not: that the Polyhedron is not going to save this town. At best, the tower is an empty promise of salvation, and at worst, it is an industrial parasite upon the land.

Where the Bachelor’s ideals were embodied by the Polyhedron, yours are captured by the Town’s other architectural megastructure: an ancient Kin temple of the earth called the Abattoir. This zoomorphic structure is an extension of the land itself and predates every other structure in the Town. However, the Town’s industrialization has forced the Kin to make sacrifices. Your father sent you to Western medical school instead of training you as his apprentice, and the Abattoir was converted from a holy place to an industrial slaughterhouse. You, the Abattoir, and the Town itself are all a mix of tradition and progress, natural and manmade. Conflict is unavoidable.

Atop the Abattoir sits another structure—the monumental housing project called the Termitary. Many of the Kin, who once lived out on the steppe, are confined to the Termitary. Again, Constructivist architectural ideas from another world seep into this one. This time, the dream is of a housing project called Narkomfin that revolutionized living for Soviet workers in the late 1920s.8 Narkomfin provided everything needed for the daily life of its inhabitants: sleeping quarters, rooftop garden space, a library, kitchens, a rec room, laundry services, and more. The architecture condensed the lives of its inhabitants into a communal experience under one roof. Through the promotion of communal living, this Constructivist project aimed to further the revolution by turning its inhabitants from individuals with separate private lives into dedicated socialist party members in every aspect of life.

The Termitary embodies the failure of the utopian Narkomfin project. Like the Polyhedron, the Termitary was built by a powerful and wealthy family—the Olgimskys—as part of an industrialization project to revolutionize the Town. The building is a monument to the modernization, industrialization, and colonization slowly eroding the nomadic Kin way of life. The Termitary houses all of the Abattoir’s Kin workers under one massive concrete roof, and as the plague descends upon the town, the Kin workers are isolated inside. Theoretically, the building should provide them with everything they need to survive in an isolated utopian existence of productivity and efficiency. However, true isolation from the outside world is impossible. Plague infiltrates the Termitary anyways, and the workers’ isolation and close quarters dooms them instead of saving them.

You, the Haruspex, see that utopia comes with a human cost. The architectural future imagined by the Town’s ruling families comes at the cost of the Kin-- both their way of life and their lives. By definition, utopia is exclusionary, and there will be no room for the Kin in the new world. The Termitary dooms the Kin people, and you discover that your suspicions about the Polyhedron were right; it is a parasite that penetrates into the very heart of the Earth itself, quite literally killing the living land that is sacred to your people and unleashing a deadly plague as punishment. This time around, you get to decide the fate of the Town. Like the Bachelor before you, you do not hesitate, only this time, you make a different choice. The Polyhedron dies, and dreams of Constructivist utopia die with it.

And, scene! Let’s take one last read through the script. With feeling, this time! Changeling, take the stage.

- Theatrical

You are the Changeling, but sometimes the others call you Clara—just Clara. It would be ridiculous to give a doll a last name. You see the truth of this world now: it is not a real place and you are not a real person. This is a game in a children’s sandbox of make-believe, and you are simply a vehicle for storytelling. The structures of the Town are characters that participate in the narrative just as actively as its human inhabitants. The Town itself is a character too, sick with a plague of ideological conflict. The Polyhedron and Abattoir stand opposite each other upon the set of this architectural theater. Every conflict in the town can be summed up by this dichotomy—the tower versus the earth, the scientific versus the spiritual, the future versus tradition.

You were waiting in the wings during the last two performances, and you know that this game always ends with a choice. The previous leads saw the town through their own lens of experience. The high-minded Bachelor chose his miracle tower, consequences be damned, and the practical Haruspex ignored the possibility of a better world in favor of saving those he could. You, however, are a child spawned into existence as a blank slate the moment the plague began. The biggest influence on your decision is not your preexisting life philosophy but rather the previous results of the game. You do not want to pick a side. You are neither the Polyhedron nor the Abattoir. You are the Theater, embodying the fictional nature of the world itself.

You do not solve the Town’s conflict by making a concrete decision that would end the game. A small number of your Townsfolk followers sacrifice themselves in an act that leaves the Polyhedron and the Town both miraculously unscathed in a deus ex machina that continues the ideological conversation between the two sides indefinitely. The purpose of this game is not to conclude the conversation; the act of participation itself is its own end. So, you preserve the Town in a constant state of balanced tension.

There is only one more scene left before the end of the play. You return to the Town’s Theater, the place where the fiction of this world is most obvious. Two actors stand upon the stage. They tell you what you already know, that “Clara is the game’s main protagonist. And so is the Dirt… so is the Utopia.”11 Through this conversation, the architecture of the Town as a stage is explicitly revealed. But then, the actors take the conversation one step further by speaking directly to you, the player.

- Digital

Clara believed that the game was played in a sandbox by the children called The Powers that Be. She was wrong. The actors explain, “The hero is a doll, but so are the children. The real game is what is happening between you and us.”11 They are no longer speaking to a character, and you are no longer playing a role. You are inside a digital avatar, speaking to the developers of this world from the game studio Ice-Pick Lodge. They tell you, “It was the town that had been built for you, not the other way around.”11 The world of Pathologic is a fully designed and constructed digital space created for the sole purpose of furthering the game’s narrative. This is game space.12 Pathologic is an example of a game at the intersection of architecture and fiction because its story and its game space cannot be separated from one another.

In a way, game space is comparable to the original Utopia. The developers of Pathologic even joke about this in their creation’s name. The original Russian title of Мор. Утопия (Mor Utopiya)—literally “plague utopia”—is a tongue-in-cheek reference to Thomas More’s 1516 book Utopia13, which invented the concept of utopia as we know it. With a name derived from the Greek ou- (not) and -topos (place), More’s island of Utopia is an idealized, imaginary society completely isolated from outside influence.14 Game space certainly fits this qualification of utopia as a non-place. The Town’s society itself is not utopian, but the isolation of game space creates the perfect conditions for game writers telling a story. There is no inherent sense of place in game space, so writers can define it however they want. The steppe surrounding the Town plays the part of the vast ocean around More’s island of Utopia, separating it from the rest of human society. More importantly, the steppe is simply the graphic representation of the fictional world’s bounding box—there is no continuation into a world beyond. Crossing this boundary and entering the town requires you, as the player, to make a journey between real space and game space where you psychologically inhabit a digital character. As Professor Janet Murray of Georgia Tech explains, “We seek the same feeling from a psychologically immersive experience that we do from a plunge in the ocean or swimming pool: the sensation of being surrounded by a completely other reality, as different as water is from the air that takes over all our attention, our whole perceptual apparatus."15 When you play a game, you enter the world of game space.

The game space architecture of Pathologic is most similar to that of a theme park like Disneyland. In philosopher Louis Marin’s analysis of Disneyland as a utopic space, he argues that “the visitors to Disneyland are put in the place of the ceremonial storyteller.”16 From the romanticized past of Frontierland to the retrofuturist promise of Tomorrowland, each zone of Disneyland represents a different facet of the idealized American identity. Experienced as a whole, the park is an architectural narrative about the American dream. Each visitor might have a unique experience exploring the park, but the overall end effect is the same across all experiences. Narrative video games, including Pathologic, function in much the same way. The game’s story provides branching choices and the illusion of player control, but the overall story and its themes remains constant.

Game space gives the game designer—the digital architect—complete control over their world and its inhabitants, including players like you. You might comment on this to the developers if you happen to meet them while playing as the Bachelor, saying, “I cannot leave Bachelor’s body. You are imposing your limits upon me.”11 Your paths of exploration and progression through the story are dictated by architectural limits: the Town’s invisible border, locked doors, and long walks from one landmark to another. Architectural aspects such as lighting and materiality are directly imbued with narrative beyond what is possible in the real world; for example, infected districts of the Town are covered with tumor-like textures and overcast in sickly light. Game architecture like this exists only for the purpose of creating a player experience. However, in order to create a controlled, digital world, designers need to abstract the complexities of the real world. This raises the question: if games are only an approximation of reality, then what value do they have in reality?

- Physical

Once you close out the game window, you transition from game space back to real space. However, according to German filmmaker and artist Hito Steyerl, the logic of game theory still dictates our reality. In a lecture she gave in Barcelona, Steyerl explained that “most people think [video games] are unreal or just pure fictions or distortions of reality. The opposite of that is true. Games are reality.”17 Over the past hundred years, economic and military simulations have greatly influenced the development of society. These models act as guides for human decision making, and games that follow similar rules basically act as behavioral training for people. However, models are inherently imperfect representations of reality. Steyerl argues that our obsession with aesthetically beautiful yet flawed models is what led to the 2008 Financial Crash. If the risks are so high, one solution is to simply treat simulations as if they exist in an autonomous realm with no influence on our world; game space and real space are mutually exclusive.

However, ultimately, Steyerl reaches a similar conclusion to the one reached in Pathologic: the act of creating and engaging with generative fiction is a valuable tool for influencing reality. Within the narrative of the game, the models of success produced by the Bachelor and Haruspex are both flawed. After seeing the failure of their solutions, the player must choose to return to the game once more as the Changeling and create a new ending outside the existing options. This falls in line with Steyerl’s philosophy that “You will have to imitate a not-yet-existent reality and game it into being.”18 The application of this philosophy to the physical world promises to create new and creative solutions outside our reality’s existing system of models.

1 McLeroy, Carrie. “History of Military Gaming.” U.S. Army, August 27, 2008. https://www.army.mil/article/11936/history_of_military_gaming.

2 Česnauskas et al. Pathologic 2: Artbook. Ice-Pick Lodge, 2019.

3 “Russian Revolution.” Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, March 6, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/event/Russian-Revolution.

4 Lodder, Christina. Russian Constructivism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

5 “Inventing Abstraction.” MoMA. The Museum of Modern Art, December 23, 2012. https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2012/inventingabstraction/?work=226.

6 Siegelbaum, Lewis. “Comintern.” Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. Michigan State University , January 4, 2016. https://soviethistory.msu.edu/1921-2/comintern/.

7 Rummel, R. J. “61,911,000 Victims: Utopianism Empowered.” Lethal Politics. University of Hawaii . Accessed March 22, 2023. https://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/USSR.CHAP.1.HTM#:~:text=In%20sum%2C%20probably%20somewhere%20between,the%20table%20(line%2094).

8 “Utopian Dreams.” World Monuments Fund, 2006. https://www.wmf.org/publication/utopian-dreams.

9 Vronskaya, Alla. “Making Sense of Narkomfin.” Architectural Review, July 24, 2020. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/making-sense-of-narkomfin.

10 Ice-Pick Lodge. Pathologic 2. tinyBuild. Windows PC. 2019.

11 Ice-Pick Lodge. Pathologic Classic HD. Good Shepherd Entertainment. Windows PC. 2015.

12 McGregor, Georgia Leigh. “Situations of Play: Patterns of Spatial Use in Videogames .” Essay. In Proceedings of the 2007 DiGRA International Conference: Situated Play 4, Vol. 4. Tokyo: University of Tokyo, 2007.

13 Чимде, Олег. “‘Иногда Выгоднее Проиграть Войну, Чем Выиграть Её’: Большое Интервью с Ice-Pick Lodge ‘Море.’” DTF, August 23, 2019. https://dtf.ru/gamedev/65410-inogda-vygodnee-proigrat-voynu-chem-vyigrat-ee-bolshoe-intervyu-s-ice-pick-lodge-o-more. Note: Interview in Russian with Pathologic 2 director and writer Nikolai Dybovsky.

14 “Thomas More's Utopia.” The British Library . Accessed March 22, 2023. https://www.bl.uk/learning/timeline/item126618.html.

15 “Understanding Immersion.” University of Stavanger, January 6, 2022. https://www.uis.no/en/research/understanding-immersion.

16 Marin, Louis. “Utopic Degeneration: Disneyland.” Essay. In Utopics: Spatial Play, translated by Robert A Vollrath, 239–57. Humanities, 1984.

17 Steyerl, Hito. “Why Games? Can People in the Art World Think?” LOOP Festival. Lecture presented at the LOOP Festival, June 8, 2016.

18 Steyerl, Hito. “Can Creatives Think?” New Left Review, no. 103 (2017).